Since the global financial crisis in 2007-08, central banks have kept their monetary policy exceptionally loose, particularly in more advanced economies, in order to support a recovery that is slowly taking place, an economist at KCIC said.

Camille Accad, economist at Kuwait China Investment Company (KCIC) said central banks have employed two main policy tools: (a) keeping policy interest rates low and (b) purchasing assets such as bonds, resulting in increased demand for bonds, higher prices and hence lower yields.

The G3 central banks, the US Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of Japan (BOJ), have already slashed their key policy interest rates to near zero levels.

The Fed and the BOJ are both injecting liquidity through asset-purchasing programs, and the ECB might follow soon. The overall result is an environment of particularly low market interest rates. Given the stronger global financial and trade links, emerging economies have also benefited from those low interest rates.

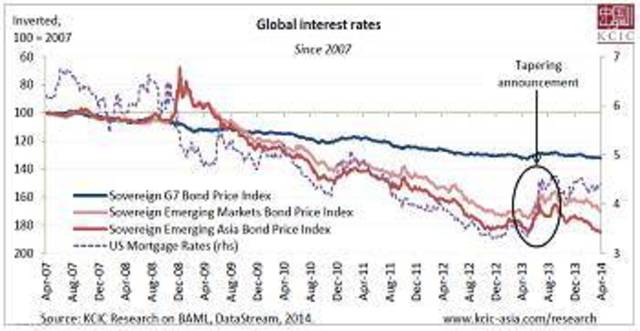

The Bank of America Merrill Lynch (BAML) bond price indices clearly show the context of low rates. These indices track demand for bonds, and they increase when demand and price rise.

Because bonds offer a fixed payment, higher prices imply lower returns, or interest rates, being offered by those bonds. In the graph we invert the price index, therefore capturing interest rate trends on bonds.

The BAML sovereign bond price index for G7 economies (US, UK, Germany, France, Italy, Canada and Japan) has significantly increased since the crisis. Because of the inverse relationship between bond prices and yields, the gradual increase in bond prices implies that yields, and interest rates, have fallen in the G7.

The strong demand for G7 sovereign bonds is a clear indication that although liquidity is abundant, investors are still cautious about financial markets.

Markets have shown an increased interest in inherently safer sovereign bonds. Since the 2007-08 global financial crisis, G7 bonds have gained more than 30% in value. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) has also been forced to keep rates low due to the majority of its members’ currency peg to the US dollar.

Despite relatively higher central bank policy rates and the absence of any asset-purchasing program, emerging markets’ interest rates have also come down. According to BAML, emerging market sovereign bonds have demonstrated a similar trend to that of the advanced economies.

Emerging market sovereign bond prices have increased by more than 60% since mid-2007. Emerging Asia outperformed its emerging market peers, having gained more than 80% in value in that period.

This is very positive for the global economy as it also indicates a sense of confidence from the lenders that their loans to emerging market sovereigns, especially emerging Asian governments, will get paid back.

More importantly, low sovereign bond rates mean that inflation expectations are still low. Lenders are willing to receive lower interest rates on their long-term advances because they don’t expect inflation to bounce back and reduce their interest gains any time soon.

The ongoing below-potential growth environment is the main reason why inflation expectations are still low – forcing central banks to buy more assets in order to keep interest rates low.

In this context, inflation is a major threat. If inflation starts to pick up again while economies continue to grow at subpar levels, the natural increase in interest rates could further dampen the sluggish economic growth. Such a scenario could occur if energy or agricultural prices rebounded due to idiosyncratic reasons.

Although chances are low, earlier-than-expected inflation is still a possibility that could cause central banks to cut on their stimulus programs, leading to higher interest rates and diminishing global output.

In May 2013, Federal Reserve Chairman at the time Ben Bernanke claimed there was an increasing likelihood that the central bank’s third quantitative easing program (QE3) may be reduced.

Even though the actual reduction would still take eight months to start, the announcement drove rates sharply higher in the US, in both the benchmark treasury yields and the mortgage rates, as well as in the rest of the world, especially in emerging markets. Since then, rates have come down, but any sign of inflation, which could trigger the end of the stimulus, could spike rates around the world again.

Higher interest rates would hurt the global economy. Emerging markets would suffer, since higher rates in the United States would make their returns less attractive, forcing central banks to increase interest rates to prevent money from leaving the country. But also the United States would be affected: demand for mortgages would decrease, affecting the housing sector, one of the most resilient drivers of growth in America. Some signs of deceleration are already showing up and this is why we think that the Federal Reverse might have to slow down the pace of reduction of its asset-purchase program or even stop it. Low interest rates will be prevalent for some time because the world is not strong enough to stand without them.

Camille Accad, economist at Kuwait China Investment Company (KCIC) said central banks have employed two main policy tools: (a) keeping policy interest rates low and (b) purchasing assets such as bonds, resulting in increased demand for bonds, higher prices and hence lower yields.

The G3 central banks, the US Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of Japan (BOJ), have already slashed their key policy interest rates to near zero levels.

The Fed and the BOJ are both injecting liquidity through asset-purchasing programs, and the ECB might follow soon. The overall result is an environment of particularly low market interest rates. Given the stronger global financial and trade links, emerging economies have also benefited from those low interest rates.

The Bank of America Merrill Lynch (BAML) bond price indices clearly show the context of low rates. These indices track demand for bonds, and they increase when demand and price rise.

Because bonds offer a fixed payment, higher prices imply lower returns, or interest rates, being offered by those bonds. In the graph we invert the price index, therefore capturing interest rate trends on bonds.

The BAML sovereign bond price index for G7 economies (US, UK, Germany, France, Italy, Canada and Japan) has significantly increased since the crisis. Because of the inverse relationship between bond prices and yields, the gradual increase in bond prices implies that yields, and interest rates, have fallen in the G7.

The strong demand for G7 sovereign bonds is a clear indication that although liquidity is abundant, investors are still cautious about financial markets.

Markets have shown an increased interest in inherently safer sovereign bonds. Since the 2007-08 global financial crisis, G7 bonds have gained more than 30% in value. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) has also been forced to keep rates low due to the majority of its members’ currency peg to the US dollar.

Despite relatively higher central bank policy rates and the absence of any asset-purchasing program, emerging markets’ interest rates have also come down. According to BAML, emerging market sovereign bonds have demonstrated a similar trend to that of the advanced economies.

Emerging market sovereign bond prices have increased by more than 60% since mid-2007. Emerging Asia outperformed its emerging market peers, having gained more than 80% in value in that period.

This is very positive for the global economy as it also indicates a sense of confidence from the lenders that their loans to emerging market sovereigns, especially emerging Asian governments, will get paid back.

More importantly, low sovereign bond rates mean that inflation expectations are still low. Lenders are willing to receive lower interest rates on their long-term advances because they don’t expect inflation to bounce back and reduce their interest gains any time soon.

The ongoing below-potential growth environment is the main reason why inflation expectations are still low – forcing central banks to buy more assets in order to keep interest rates low.

In this context, inflation is a major threat. If inflation starts to pick up again while economies continue to grow at subpar levels, the natural increase in interest rates could further dampen the sluggish economic growth. Such a scenario could occur if energy or agricultural prices rebounded due to idiosyncratic reasons.

Although chances are low, earlier-than-expected inflation is still a possibility that could cause central banks to cut on their stimulus programs, leading to higher interest rates and diminishing global output.

In May 2013, Federal Reserve Chairman at the time Ben Bernanke claimed there was an increasing likelihood that the central bank’s third quantitative easing program (QE3) may be reduced.

Even though the actual reduction would still take eight months to start, the announcement drove rates sharply higher in the US, in both the benchmark treasury yields and the mortgage rates, as well as in the rest of the world, especially in emerging markets. Since then, rates have come down, but any sign of inflation, which could trigger the end of the stimulus, could spike rates around the world again.

Higher interest rates would hurt the global economy. Emerging markets would suffer, since higher rates in the United States would make their returns less attractive, forcing central banks to increase interest rates to prevent money from leaving the country. But also the United States would be affected: demand for mortgages would decrease, affecting the housing sector, one of the most resilient drivers of growth in America. Some signs of deceleration are already showing up and this is why we think that the Federal Reverse might have to slow down the pace of reduction of its asset-purchase program or even stop it. Low interest rates will be prevalent for some time because the world is not strong enough to stand without them.

Source:

Mubasher